Ivan Vucetic (real name) was born on July 20, 1858 in Lesina, a town on the Serbo-Croatian island of Hvar in the Dalmatian archipelago, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the son of Victor and Vicenta Kavacevic. He arrived in Buenos Aires from overseas in 1882 and it was known that his preferred art was music. Although he had no pretensions in anything, he immediately wanted to start some kind of business.

Soon this young man was working as a foreman at the Obras Sanitarias, responsible for supervising the work of a certain number of workers and diligent in the performance of his duties.

In 1888, Vucetich moved to the city of La Plata (Buenos Aires) and joined the Buenos Aires Police, where, by order of the Chief of Police, Don Carlos Costa, he was assigned to the Statistical Office and put in charge of the Anthropometric Identification Department, since it was attached to this office, Vucetich immediately began to prepare a preliminary project for the complete reorganization of this service. It can be recalled that in mid-1891 he worked on the organization of an identification service using the Anthropometric System based on the method of the Frenchman Alfonso Bertillon, which took into account the dimensions of certain bones: The size of the skull, the length of the middle finger, the left foot and the forearm constituted his standard of measurement to identify people. Apart from Argentina, only the United States, Canada and France had this type of office.

Photo identification was not well developed in the country because it was expensive and artists were used to make drawings of suspects’ faces.

Vucetich corresponded with Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s cousin, an Englishman who had done interesting work on heredity, laid the foundations of eugenics, and devoted himself to statistics, criminology and the study of a rich universe of the constancy, diversity and continuity of fingerprints.

Galton was not the first to emphasize these things. When the Czech physiologist Jan Purkinje discovered that the tips of the fingers and soles of the feet do not change from birth to death, he had taken up the thread of observations going back to antiquity.

Fingerprints have been studied by various cultures who have recognized their benefits. In Korea, slave traders had slaves’ five fingerprints stamped on paper to document a sale. The Chinese used fingerprints to sign contracts.

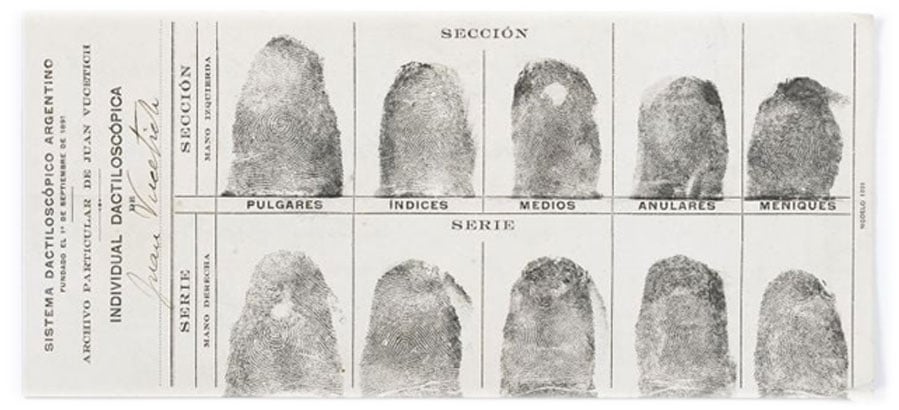

Fingerprints were kept from birth to death. At the age of 33, Vucetich was able to identify 101 features, which he divided into four groups: arches, inner and outer rings and folds. He called this system Ichnophalangometric and it came into use on September 1, 1891. This almost unpronounceable word was changed to Dactyloscopy by Vucetich at the suggestion of the scientist Francisco Latzina.

What is Icnofalangometry?

The science of Dactyloscopy, originally called “Icnofalangometry”, is a procedure for individual identification based on the examination of drawings of the fingertips of the hands printed on paper or cardboard.

Vucetich started by identifying 23 defendants and then went on to identify all the inmates of the La Plata (Buenos Aires) prison. The following year it was the turn of police cadets. Based on his methodology, he found that eighty of them had criminal records and that there were others hiding under another identity.

The first-time fingerprints helped solve a case was on June 29, 1892, in Necochea, Buenos Aires. The police were shocked because they weren’t used to crimes like the murder of two young children, Felisa and Ponciano, aged four and six. Their mother, Francisca Rojas, had a superficial wound on her neck and was determined to incriminate a man who swore his innocence even when he was vigorously questioned by the police. Inspector Eduardo Álvarez, searching for tracks, fingerprints, and other remains, found some bloody fingerprints on the door of the house and sent them to Vucetich. Applying his own method, Vucetich eventually proved the guilt of the woman, who confessed that she had preferred to kill her children rather than hand them over to her estranged husband, faked an attack, and blamed a humble neighbor in the area where the crime was committed.

Thus, we can say that Juan Vucetich was the first to apply the principles of the Scientific Police in the province of Buenos Aires. So far, history wants Vucetich, with 33 years of young life, to have achieved a success that transcended the borders of his adopted nation (Argentina).

Vucetich worked non-stop. He took samples from prisoners and when he obtained more than 3,600 records, the police finally adopted his method in 1894.

Public servants, coachmen, carriage drivers, domestic servants and prostitutes, among others, had to register with the police and were fingerprinted.

By 1903, there were 600,000 registrations, and from the beginning of the 20th century these registrations began to appear in personal documents. With compulsory military service, every man who joined the army had to be registered.

With a cylinder, black ink and a “pianito”, anthropologist and policeman Juan Vucetich painted the fingertips of the hands of 23 prisoners in the city of La Plata and created the first personal identification cards. He tried to solve the problem of identifying criminals and their level of recidivism.

This event took place 130 years ago, on September 1, 1891, and marked the beginning of the development of the Argentine dactyloscopic system that would later spread around the world. This system was adopted in other parts of the world.

Why do you think it prevailed over other existing identification techniques?

This system had several advantages for the mass identification of the population, it required fewer human resources, the tools and equipment were cheaper and very simple, it was easy to implement in large areas. It allowed for positive identification, it was not a probabilistic system like the anthropometric system. Its classification was much more complex but centralized. For example, Vucetich classified all the fingerprints in the province of Buenos Aires. The prints came by mail to the central department in the city of La Plata, where Vucetich had an archive of prints from the entire province and a small team dedicated to classification.

Vucetich’s work was not limited to criminal matters; he also promoted the need for civil identification based on ID cards, for example, and was responsible for the massive identification work for the implementation of the Sáenz Peña law* and the creation of the first fingerprinted lists.

Over time, this multifaceted pioneer began to move away from police matters and think more about civilian identity, identity as a right, the creation of documents to guarantee the right to vote, and finally left the police force in 1912. He later supported the creation of a civil identity archive in the Province of Buenos Aires and the enactment of the Sáenz Peña Law on universal, legal and compulsory suffrage.

The creation of the first document to include fingerprints was another important point in Vucetich’s career. With the Sáenz Peña Law, fingerprinting was mandatorily included in the Libreta de Enrolamiento, a document related to enrollment in military service, which already existed but contained some information about the person. This booklet would now include the fingerprint, and 10 fingerprints would also be taken and kept on file.

Here is the chronological order of importance of the implementation of this system and Vucetich’s life:

1892 – For the first time in the world, a person was convicted for being fingerprinted (Francisca Rojas case).

1896 – Vucetich unveils his new system of four basic types, which gives rise to the “ARGENTINE DACTILOSCOPIC SYSTEM”.

1912 – Vucetich retires from public service and begins a study tour around the world.

1925 – He dies on January 25 in Dolores, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina.

What remains of the technique developed by Vucetich?

Fingerprint identification is still used today in both civil and criminal matters. One tends to think that one system is superior to another, but research shows that different systems often overlap and have different uses. For example, photo identification is still in use today, anthropometric measurements, although not the same as those used by Bertillon, are still widely used today because facial recognition programs are based on body measurements, and the advent of DNA did not mean the abandonment of fingerprinting.

Today, a number of methods are used in combination, serving different purposes in various situations. Particularly in forensic and criminal investigations, the examination and collection of evidence from crime scenes is vital. In these processes, the detection and analysis of important evidence, such as fingerprints, plays a critical role in solving crimes or identifying guilty parties.

Traditionally, methods such as dusting and chemical spraying have been used to make fingerprints visible. However, these methods have some disadvantages. For example, the dusting process used to reveal fingerprints can prolong the time it takes to find them and, in some cases, can lead to damage or degradation of the prints. In addition, while the use of chemicals can help to recover prints, it can also lead to the loss or contamination of other important evidence, such as DNA.

To address such issues and provide a more effective method, non-contact fingerprint imaging technology has been developed. This technology is specifically designed to image fingerprints on contact surfaces. Most importantly, this method does not require any physical contact to reveal fingerprints, which prevents contamination and enables more precise analysis.

ForenScope has produced the world’s first mobile device to develop and improve non-contact fingerprint imaging technology. This technology is supported by the use of powerful lights and high-resolution cameras, resulting in flawless fingerprint imaging. This method has become an important tool in forensic processes, making it possible to examine and analyze fingerprints in detail.

ForenScope devices boast cutting-edge, exclusive technologies in forensic imaging. They stand out for their user-friendly design, portability, powerful lighting, and filters, as well as their high-quality, high-resolution images. Moreover, they feature specialized software allowing for the organization of case files, where essential details like names, numbers, and relevant information can be easily inputted. Additionally, these devices automatically timestamp and geotag each file, avoiding the mix-up of images typical with standard cameras and facilitating the creation of a well-organized case library.

As a result, ForenScope’s non-contact fingerprint imaging technology offers a more effective and reliable option compared to traditional methods. It plays an important role in forensic and criminal investigations and is invaluable for both solving crimes and delivering justice.

*The Sáenz Peña Law (Spanish: Ley Sáenz Peña) was the Argentine Law 8871 , approved by the National Congress on February 10, 1912, which established universal, secret and compulsory male suffrage through the creation of an electoral list (Padrón Electoral).